How Unmasking Empowers Autistic Leaders: What I Learned by Refusing to Play the Game

Blog at a Glance:

Discovering I'm autistic wasn't just a diagnosis; it was a profoundly liberating experience reflecting Resmaa Menakem's concept of "clean pain." In this deeply personal post, I explore my journey of unmasking – shedding the exhausting "dirty pain" of conforming to neurodominant expectations that never truly included me. I delve into why masking largely fails for Autistic people, especially those holding marginalized identities, and how the constant pressure to assimilate is a rigged game offering little reward. Drawing parallels to James Baldwin's insights, I challenge the harmful myth that progress means becoming "less autistic." Instead, I advocate for radical authenticity: designing lives aligned with our neurodivergent needs, setting boundaries, and demanding space. As an intersectional neurodiversity coach, I share how embracing this "clean pain" empowers us to thrive, connect meaningfully, and build communities where we truly belong. Read the full reflection on my journey below.

If you're familiar with Resmaa Menakem’s powerful novel “My Grandmother's Hands”, then you are likely aware of a concept called somatic opening or what he terms clean pain. The author talks about clean pain as opposed to dirty pain and describes clean pain as the process of unlearning and discovering parts of oneself and facing truths that allow one to expand and become more alive, and for the body to become more alive. In contrast, dirty pain is the discomfort and the challenges we go through as we attempt to stay the same or maintain the shape that we have in our life to maintain expectations that were imposed on us.

And typically, there are many challenges that come with transition and learning that one is autistic. In my experience, it was one of the most impactful and life-changing experiences that I've ever had to go through. So much is made more transparent, and so much comes into focus and makes more sense when one discovers that they are part of the autism spectrum. This is not everyone's experience, of course. It is mine, though. And a lot of that process has to do with unlearning the maladaptive behaviors that I took on in negotiation with an environment that was, at best, barely tolerable towards me, and, at worst, was openly hostile to my very ways of being.

It's very disconcerting to go through one's experiences in life from the age of around 9 or 10 and to be able to sense that your very way of being perturbs others, but to have no clear understanding of why that is. It is even more troubling when you observe that the other people have no idea why they don't like you either. I've noticed a sort of cognitive dissonance that comes about when people, especially young children, see you doing what you're supposed to do, being the way you're supposed to be, and yet they can't help but feel like there's something off about you.

And so adults who are parents or caregivers or teachers who see this occurring are also perturbed and out of either discomfort or desire to help, they often attempt to encourage the child to conform to expectations more forcefully, to double down, or triple down, in hopes that the outsider will be welcomed in. They can't quite grapple with the reality that neurodominant people are not mad at us, they're mad that it's us. Meaning that neurodominance itself is challenged and under threat by the radical acceptance and authenticity displayed by successful and visible autistic people.

We know what others expect of us, and many of us choose authenticity over attachment to neurodominant culture. There's nothing that we've done or said or that we didn't do that is the cause of our exclusion and lack of belonging within neurodominant spaces. And so as a coach of autistic people, I've been blessed to help people unmask and re-discover who they are and what brings them joy, and what life they can design for themselves that is in full alignment with their authenticity.

It is possible to be authentic and to survive and to connect with others and to make a living and to find love. In spite of the words of our current health and human secretary, RFK Jr, autistic people fall in love and connect with others, make meaningful contributions, and make art every single day, as we've done since time immemorial and as we'll continue to do as long as humanity exists. It is well past time that we realized that Allistic (non-Autistic) masking is not a viable strategy for Autistic people.

Moving closer to the normalized way of being, communicating, or thinking only puts those with unearned disadvantages at risk and solidifies the centrality of those who are centered within our systems. It is always those who are well fortified and secure in their sense of belonging and power who insist that the mark of progress is how well others can attain proximity to their likeness. I’m reminded of the words of the Great American social critic, orator, and author, James Baldwin, who remarked that to white America, the measure of progress for a Black person is how fast they can become White.

This is not too dissimilar, broadly speaking, from the expectations that exist for autistic people and many other people who are disabled cognitively, physically, socially, and medically. There is a shift occurring, though. There are those of us who are looking around at the crumbling systems and noticing gaps and spaces that are beginning to emerge where neurodivergent folks can exist, connect, grow community, and be ourselves. We exist. As we always have and always will.

Systems will come and go. Medical definitions will arise and decline in popularity. But we will endure. We are the descendants of the people who were thought of as shamans in the old world and those who were believed to walk the gates between the other world and this one. There have always been people who see things that others do not see and are more sensitive than those around them, and can notice patterns where others cannot. Our words may change when describing this experience, but this reality has always existed.

And so this belief or this pervasive idea within the popular discourse that there are more people who are becoming or who are discovering that they are autistic is flattening the richness and the radical potential of this moment. From my perspective, what is also occurring is that people are shifting and taking back power from institutions about how they should feel about their lived experience and who they are, and what that means for their lives. There is a process of becoming and unbecoming that co-occurs.

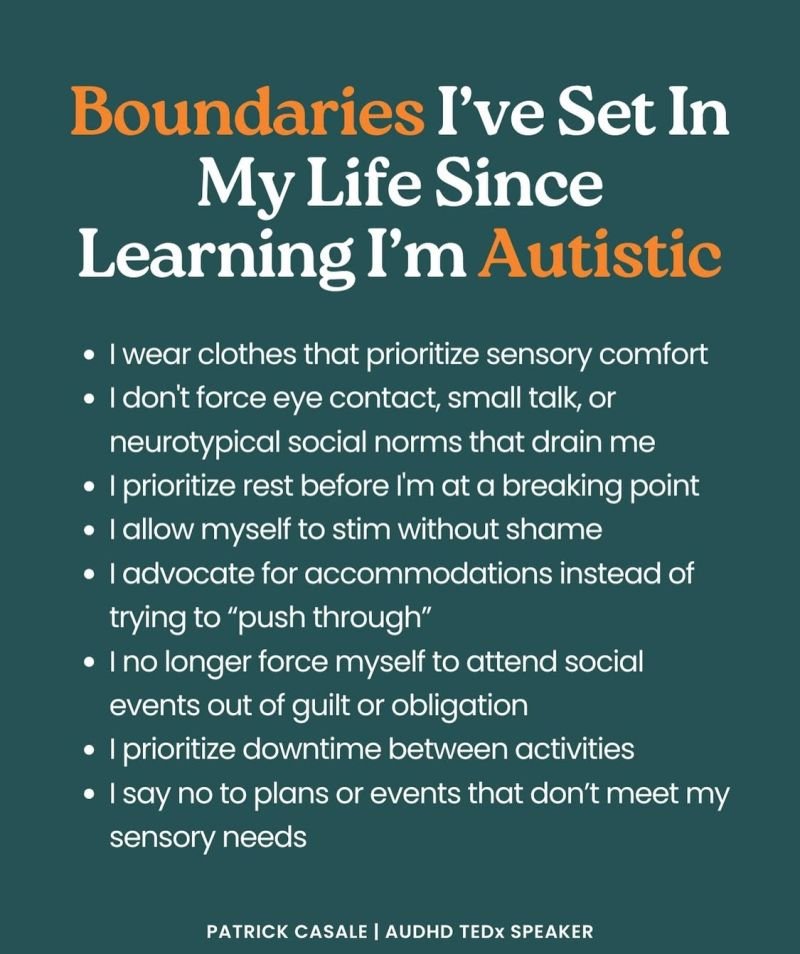

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. I've noticed that as people are coming to understand that they are potentially Autistic or have other neurodivergencies that are part of their identities, they are beginning to question what it even means to be neurodivergent or to be autistic. The personal is the political. When we change our shape and our way of thinking about ourselves, we change more than ourselves. When we put forth our own definitions, terms, and culture, hold fast to our boundaries, and vocalize our needs, it is an invitation and a demand for space and dignity.

I don't know what this all means, but I can share my experience and some of the lessons that I've learned as I have personally engaged in the process of unlearning and welcoming a recommitment to my authenticity in exchange for the self-limiting idea that I need to engage in neurodominant culture as a safety strategy.

One of the most potent lessons I’ve ever learned in discovering that I am autistic is that I don’t have to abide by social norms or neuro-dominant expectations, in large part because I don’t get the benefit others get when they do. When I realized that I don’t get the same benefit of the doubt or reciprocity when I do things like give eye contact, or engage in small talk, or stay at an event, even though I’m not enjoying it, it was much easier not to do those things anymore. Why should Autistic people “play the game” if we always lose?

This goes even more so for people who are autistic and exist at the intersection of other identities with unearned disadvantages, like people of color or gender minorities. My spouse, who is also autistic and is a white male, engages in more activities that are neurodominant than I do because he and I have noticed that he gets more traction out of doing those things than I do.

In other words, the juice isn’t worth the squeeze for many autistic people. Research shows that, all things being considered, autistic people are assessed as less warm or approachable on a whole range of traits that people might think are “soft skills” from the jump. When we go out of our way to be nice, our actions aren’t interpreted as such and are not reciprocated. Allistic (non-autistic) people make snap decisions within three seconds of meeting, seeing, or hearing someone who is Autistic. Their brains interpret us as different and label us as “the other,” even if we share other identities with them.

So, masking (largely) doesn’t work. Meeting neurodominant (Neurotypical) people halfway does not always work. Minimizing and limiting discussion of our differences can actually cause more problems and misunderstandings. We’re different, and so are our needs. I can’t speak for all Autistic people, but it was incredibly empowering to realize that I wasn’t ever going to reach acceptance from neurodominant people or culture. If that’s the case, I’ll just spend more time doing what I want to do. I’ll let the chips fall where they may. Others are too.

I’m blessed to be a coach for some awesome neurodivergent people navigating difference and creating the life that they want, that also affirms their needs. If you’re looking for support or a neurodivergent speaker, I encourage you to visit my about and training pages for more information.